It’s a busy Friday afternoon at Meadowridge Library on Madison’s Southwest Side, where library staff are accustomed to fielding questions from visitors in many languages: English, Arabic, Somali, Spanish, Chinese.

Children are stopping in for after-school snacks furnished six days a week from the Youth Snack Program. Staff members like supervisor Yesianne Ramirez are helping library users with computers. Others are getting ready for the free comic day coming up.

Emily Kuster, left, with her 8-month-old son Eli, and Shay Johnson, with 5-month-old son Mehkai Blanton, attend a storytime event in the children’s area at Central Library in Downtown Madison. This month Central and Madison Public Library's other eight neighborhood libraries across the city are celebrating MPL's 150th anniversary.

Five miles away in Alicia Ashman Library, at 733 N. High Point Road, manager Marc Gartler has been working at the reference desk, helping visitors locate books and scan documents to renew a passport.

He gets a call from Central Library in Downtown Madison asking him to track down a copy of the New York Times, scan the crossword and send it over for a patron; someone else has already filled out the answers on Central’s copy. Nearby, the open children’s area is buzzing with preschoolers at play.

Madison currently has nine public libraries, each with a different personality that reflects its surrounding neighborhood and the needs of that population.

But they’re all part of Madison Public Library and this month they’ll all be celebrating Madison Public Library’s 150th anniversary.

It won’t just be a party, however.

“It’s to highlight our history, to encourage people who don’t have library cards to get a library card and come use the library,” said Tana Elias, Madison Public Library director.

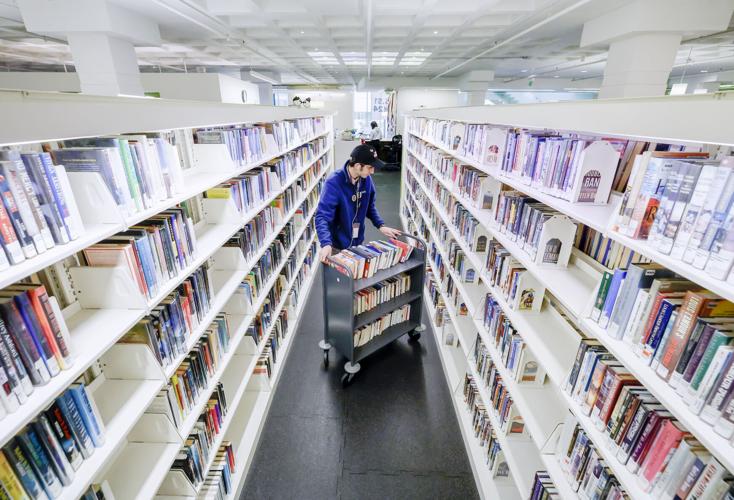

Central Library staff member Kareem Mayouf stocks the library’s shelves with returned books. More than 2.2 million items were checked out from MPL's nine libraries in 2024.

“So it’s both a celebration of the 150 years we’ve been in existence, but also to encourage people to connect with libraries if they haven’t recently, or if they haven’t been to a library before, encouraging people to learn about all the different resources we have, and all the ways we’ve changed or stayed the same over time.”

A long history

When the Madison Free Library, as it was known then, opened on May 31, 1875, it consisted of two rooms in City Hall. Only men ages 15 and up could check out a book that was pulled from the shelves by a library worker. A reading room was added in 1878 and children’s services started up in 1902. Sometime between those dates, the doors opened to women as well.

Many milestones followed over the next century and a half. According to a timeline on the library’s website, the library once ran a book station out of a grocery store (1903); helped create school libraries, serving as a model for the rest of the country (1911); built vocational collections to help returning veterans from World War I and II train for jobs (1942); and provided coin-operated typewriters for patrons (1965).

The 1980s saw a growing collection of movies on VHS tape that proved wildly popular. In 2013, the library launched the hands-on art space known as the Bubbler, which again served as a model for the nation’s libraries, and with the Madison Public Library Foundation began overseeing the Wisconsin Book Festival.

Sonny Thao and his sons Yuepheng, 9, and Shueyee, 6, use the self-checkout kiosk during a visit to Lakeview Library on Madison's North Side. Lakeview will celebrate Madison Public Library's 150th anniversary with a special program on May 31.

In 2016, MPL was one of 10 museums and libraries to receive the National Medal for Museum and Library Service, in recognition for its “customer service and civic engagement, building community involvement and promoting education and literacy.”

Through the decades neighborhood libraries popped up across the city (they’re no longer referred to as branches), outgrew their spaces, moved into new quarters and developed their own personalities. Last year, Madison Public Library’s nine locations logged nearly 1.4 million visits, up 6.8% from 2023.

Cardholders today can check out a Bcycle pass, a disc golf kit or a backpack with birding supplies. Or, of course, a book.

“When you look at the history of public libraries in America, they were imagined to be the great equalizer of sorts,” Elias said. “They were heavily influenced by the bringing of immigrants to America, acculturating them and getting them ‘Americanized,’ if you will.”

“Even in the 1880s, we were thinking about how can we serve all the new people that are in our city, and what’s the best way to do that, what kinds of services to provide,” she said.

Madison Public Library’s first branch library was opened in 1913 on Williamson Street, “in an immigrant community. And we had Saturday hours, because that’s when people were free,” Elias said.

Madison Public Library is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year.

“And we had a reading room, where people could read newspapers in their native languages,” she said. “So it’s a new and an old service. I think people think of libraries as quiet places for books, and that’s still true — we still have many books and other resources — but we’re also a place for social connection, and that has been true for many years.”

Erica Pinigis of Isthmus Dance Collective, left, leads a spring dance workshop at Pinney Library. Taking part in the event is Eden Nelson, 4. The new children's area at Pinney takes up half of the building, completed five years ago, allowing much more programming and a huge increase in visitors, library officials say.

From student page to director

Elias herself has been at the library for 32 years. Originally from Rochester, Minnesota, she came to Madison to go to library school.

“I started here as an hourly worker, a library page, when I was in grad school, then worked as a librarian at Meadowridge Library for five years,” she said. She moved to Central Library to oversee what was then the library’s brand-new website, later became its marketing director and was named library director in May 2024.

The biggest change in libraries during her career? The internet.

“When I started in public libraries, there was no internet,” she said. “It has really changed the way we provide service. It has changed the services we offer.”

Library users used to have to physically be in the building to use resources. Now they can get much of that library material online. Last year, for example, the library logged 314,867 checkouts for e-books and 352,302 for audiobooks. Its participation in the South Central Library System means that cardholders can reserve books from other libraries across the region through the LINKcat app and have the volume waiting on the shelf at their neighborhood library in a matter of days.

Today at Goodman South Madison Library, 2222 S. Park St., for example, the most heavily used resources include “technology such as fax, print, and internet and computer access,” said Goodman South supervisor Ching Wong.

Kathryn Padorr, youth services page, returns books to the shelves at Sequoya Library. Located on Madison's West Side, Sequoya has the highest number of book checkouts of any Madison Public Library. "It's our busiest library," said MPL director Tana Elias.

People “come to us for information in different ways,” Elias agreed. “Libraries provide free access to resources like, for example, the New York Times, or certain online databases. The library pays for access to those on your behalf.”

That expectation of multimedia resources, however, can push up costs. A single book title might not equal just a single print book; patrons might want it in a large-print edition, or as an audiobook or e-book. “So you have to buy twice as many, or three times as many, copies of the same thing,” Elias said.

$21 million budget

On March 19, after President Donald Trump issued an executive order that would gut the only federal agency dedicated to supporting American museums and libraries, the Madison Library filed a joint press release along with the Madison Children’s Museum “to encourage public advocacy” to save it.

The agency, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, or IMLS, funnels money to states for museums, libraries and zoos, and awards individual grants for novel projects that serve as national models (the Bubbler in Madison is an example).

Eliminating IMLS initially would hurt mostly small, rural libraries the most, said Elias, noting those same libraries are the most vulnerable to book-banning pressures.

On Tuesday, Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul announced that he and a coalition of 20 other attorneys general had secured a preliminary injunction to halt the dismantling of the IMLS and two other agencies that were also targeted in the executive order.

Mohammed Salau takes advantage of Lakeview Library’s computer resources during a visit to the Madison Public Library location on the city's North Side. Public libraries across Madison handled 140,958 computer reservations in 2024, according to MPL's annual "Year in Review." Wi-Fi sessions topped 3.5 million.

Madison enjoys a high level of local library support: The library’s annual $21 million operating budget comes mostly from property taxes, and passage of a city referendum last November meant that library services could continue at existing levels. Through contributions and grants from individuals, businesses and organizations, the Madison Public Library Foundation also provides the library with about $1 million year.

As part of the 150-year celebration, library users have been invited to write down their first memory of the library or their “wish for the library of the future” on a special piece of paper. The forms are then rolled up to resemble a candle and placed on a special fabric “birthday cake,” fashioned for the library by artist National Velvet.

On those paper “candles,” one anonymous visitor wrote a wish that the library of the future “will have reading hammocks.” Another wished for “endless funding for the library.”

Wrote another visitor: “I hope … it brings people together.”

From Wi-Fi to AC

On a recent afternoon during UW-Madison’s final exams week, university seniors Seth Gueller and Mason Smasal studied at a small table inside Central Library while they waited for a study room to open up. The two roommates come to Central regularly because it’s close to their Downtown apartment, the study rooms are spacious — and it’s quiet, they said.

When Smasal needed secondary sources for a research paper for his Roman history class, he turned to the shelves at Central Library. “If you need to print a paper, this is the place to come,” said Gueller.”Some college kids come here for that, because not everybody owns a printer.”

Three miles northeast at the Hawthorne Library, 2707 E. Washington Ave., Ron Beckwith drops in daily to read the newspaper, he said. Seated by a sunny window, his phone charger plugged into a power strip on the table, Beckwith said he has family members in Cottage Grove who lament that community’s lack of a public library.

“They’ve got to wait for the bookmobile to come around,” he said. By contrast, Madison’s public library system “is one of the best. You can check out DVDs, CDs, anything,” he said. “A lot of little towns don’t have that.”

Well over 92,000 people also visited Madison libraries last year to attend a program, from movies and jazz concerts to writing workshops and knitting circles. The library also serves those who come in during the winter seeking warmth, or in the summer needing a place to get out of the heat.

Beth Waldron of Madison, right, checks in with her daughter, Edna, 9, center, and friend, Pearl Liberatore, 8, as they read from books they picked out during a visit to Monroe Street Library. The first Monroe Street site was opened in 1944. The library moved to its current location at 1705 Monroe St. in 1960, according to a fascinating timeline created by Madison Public Library for its 150th anniversary.

Librarians today not only receive resource training, but also behavior management training, including techniques for de-escalation, Elias said.

“As we as a society see more people struggling with mental illness, with substance abuse, with a variety of different factors, keeping public spaces safe is something that we’re all responsible for,” she said. Librarians also face an ever-changing technology landscape.

“Constantly learning as a staff is really key,” she said.

Innovative thinking is, too. Madison will soon have its 10th library, expected to open in summer 2026. The $18.6 million Imagination Center at Reindahl Park, to be located on the Northeast Side off East Washington Avenue at Portage Road, is a joint project with Madison Parks. The future indoor-outdoor library and community space has been designed to serve as a neighborhood hub for some 19,000 people. It will be the city’s first library inside a park.

“Libraries really do need to be innovative,” Elias said. “As we add spaces and think about adding services, how can we best partner with either other city departments or nonprofit agencies, or other existing services, to keep the costs lower, to maybe serve more people?

“I think we have a unique opportunity at Reindahl to meet people in a different way – people who might use parks but might not use libraries, for example. Or people who use libraries but don’t use parks. They’ll get that opportunity to use both together.”

Apart from the Imagination Center, Madison Public Library’s most recent brick-and-mortar project was the construction of the new Pinney Library at 516 Cottage Grove Road. Since construction was finished at that East Side library in 2020, replacing a smaller Pinney space and offering an expanded children’s area that occupies half the 20,000-square-foot building, it has seen a “huge” increase in use by a range of people, Elias said.

“All day long families are coming in to use the space,” said Pinney Library supervisor Jane Jorgenson. More space has meant more programming. And on the adult side of the library, the study rooms are very much in demand, too, Jorgenson said. At the old Pinney there were no study rooms at all.

Circulation of materials through the building has gone up. The number of visitors has risen, Jorgenson said.

“I think public libraries are one of the last few places that you have the opportunity to meet people that are different from you,” Elias said. “You might be in a storytime program with other mothers or fathers who are very different from you, but you’re all from the same general area. And you have the opportunity to expand your horizons a little.”

“I think that’s more important now than ever, as we’ve seen information become so polarized, and information channels become more specific and targeted online,” she said. “It’s wonderful to have an opportunity to connect with people in your community around a shared resource.”