The cult of El Mencho’s image and the power of narcoculture in Mexico

Images from the Los Alegres del Barranco concert in Guadalajara open a new episode in the long series of controversies over the dissemination of symbols of organized crime

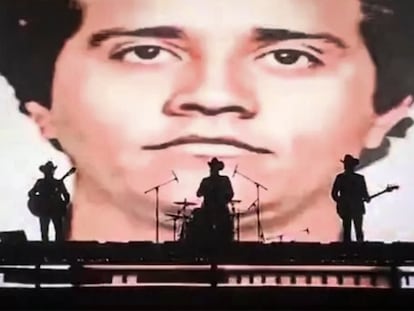

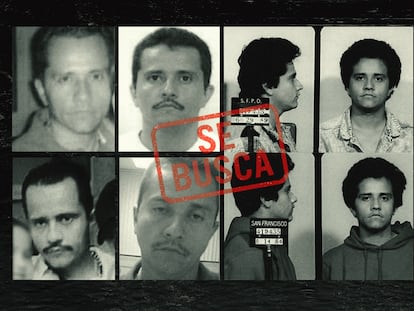

The sound of an accordion in Guadalajara covers the silence that has enveloped a ranch in Teuchitlán for weeks, the scene of horrors where the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) allegedly tortured and murdered young people. It’s Saturday, around 10 p.m., and Los Alegres del Barranco are projecting images of Nemesio Oseguera, “El Mencho,” leader of the CJNG, on the stage of the Telmex Auditorium, one of the main venues in Mexico’s second-largest city, just an hour’s drive from Teuchitlán. No one seems to remember that grim discovery. The images celebrating the cartel kingpin are the latest chapter in the long-running controversy over the reach of narcoculture in Mexican society.

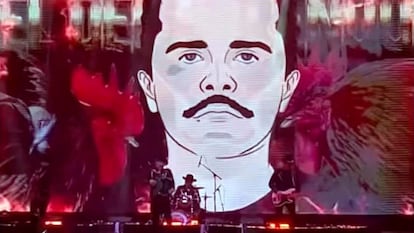

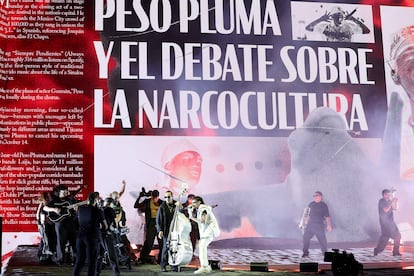

Los Alegres repeated the show a day later in Uruapan, Michoacán. Despite the media attention of recent days, projecting images of major drug lords during a concert is nothing new. Peso Pluma, star of corridos tumbados, was another example. He performed in 2022 in front of a large image of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, former leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, in Culiacán, while singing Siempre Pendientes, a song referencing the drug trafficker. Weeks later, he argued that his team was not responsible, and that the projection was the responsibility of the festival organizers.

These kinds of performances often generate controversy, but the echo of Los Alegres’ performance resonated all the way to the National Palace. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum announced the beginning of investigations into what happened that night; Jalisco Governor Pablo Lemus ordered a ban on glorifying drug trafficking in the state; and the United States revoked the visas of the four musicians. The author of Narcocultura (2024), Ainhoa Vásquez, points out that the discovery in Teuchitlán explains part of that strong reaction; and she believes that the most alarming aspect of that concert was the audience’s reaction. “It’s not so worrisome that they put up the image. The point is putting up this image, singing this song in his honor [El Mencho], and having people applaud. I found it truly worrisome [...] I wonder how heartless we have become to celebrate this, which is so incredibly real,” she reflects.

María Luisa de la Garza, a researcher at the Center for Advanced Studies in Mexico and Central America (Cesmeca), doubts that narcoculture is normalized in the country, although she believes it has a significant impact. “It’s normalized in its alignment with other values [...] But I don’t think that’s the most serious thing, because that normalization is the same as if you go to see Hollywood movies or if you go to other sites like Netflix,” she says. “[Los Alegres] could have put on the show without presenting that image, and yet they did. How powerful are those who run things in organized crime?”

The Cesmeca researcher affirms that the situation is worrying, but emphasizes the “hypocrisy” of some of the reactions to what happened. “For many years, we’ve had the same people condemning narcocorridos at a certain point, and then inviting the artists to their own electoral platform presentations,” she says. She doesn’t reveal names, but there are precedents, such as that of the businessman Armando Guadiana, the ruling party Morena’s candidate for governor of Coahuila in 2023, who sought youth support by promising to bring Peso Pluma to the state. The political party maintains a constant criticism of the musician’s lyrics.

Los Alegres del Barranco apologized days later in a video posted online. In it, they lamented that their performance had been “misinterpreted” and upsetting to some. Later, they compared their corridos to other cultural platforms: “Since our beginnings, our music has been a way of telling popular stories, just like films, photos, books, and news reports.”

A Robin Hood in the Culiacán highlands

Narcoculture has not only developed in music; there are references in paintings, films, and fiction. And it has also permeated popular imagination.

Hidden behind the green undergrowth, a man repudiated by the elite of the time dedicates himself to robbing the wealthy families of the Culiacán highlands. It’s the early years of the 20th century, and Jesús Malverde has long since set aside legality with a single goal: to steal from the rich to give to the poor. A sort of Robin Hood who personifies the double standards of those who commit crimes, yet help those in need. Legends about Malverde, never confirmed, have turned him into the Saint of Narcos. In downtown Culiacán, a chapel bears the bandit’s name, depicted with a mustache and a scarf around his neck.

Vásquez doesn’t put a specific date on the emergence of narcoculture, which also absorbed these stories: “It’s existed as long as trafficking; and trafficking has existed as long as prohibition. When it becomes an illegal business, the people involved need to create their own codes of conduct.” Research by experts like Professor Juan Carlos Ramírez-Pimienta reveals evidence of the historical support for these types of cultural manifestations. The corrido researcher highlights El Pablote (1931), a song dedicated to Pablo González, the King of Morphine in Ciudad Juárez, as the “probable” first narcocorrido in history.

Vásquez advocates differentiating between two concepts: narcoculture and narcofiction: the former, the culture produced by drug traffickers for themselves; the latter, the culture produced for the general public (such as Netflix series or the songs of certain musicians). And she believes it’s necessary to emphasize this distinction in order to find solutions: “The problem isn’t narcofiction, it’s not narco-narrative. The problem is narcoculture, which stems from drug trafficking. What we have to attack is drug trafficking, and within that, it’s essential to attack the economic pillar.”

The controversy surrounding Los Alegres led the governor of Jalisco to ban artists with a history of openly glorifying criminal activity. This measure is similar to what authorities applied on radio stations with Los Tigres del Norte in the 1980s following their album Corridos Prohibidos (1989), or about 10 years ago in Sinaloa, where they were banned after a shootout during a concert left five dead. The author doesn’t fully believe in this solution: “I don’t think censorship is a good strategy in any case. There are several states that have banned narcocorridos, and trafficking hasn’t ended. I wish it were that simple.”

During the conversation, De la Garza recalled one of the texts she wrote in 2008. In it, she proposed an alternative approach to addressing the controversy: “We have to be willing to listen to these songs — not just to expose our prejudices about them — to understand what they tell us about ourselves. Narcocorridos also talk about other things, like miserable lives, loneliness, and the gang that replaces the family. There’s a lot to be learned in that regard about the expectations of our youth.”

We have to be willing to listen to these songs — not just to expose our prejudices about them — to understand what they tell us about ourselves”María Luisa de la Garza, researcher

The sound of the accordion hasn’t stopped playing during Los Alegres’ song: “I am the owner of the palenque, four letters go up front, I am from the very Michoacán, where Tierra Caliente is, I am the lord of the roosters, the one from the Jalisco Cartel.” Two days later, the controversial performance will be front-page news in Mexico. Vásquez tries to find a silver lining in the images: “One of the positive things it brought was the outrage of the people. Social media didn’t remain silent despite the public’s backlash. It’s an outrage that can be leveraged to start talking about the issue.” Silence returns to the Teuchitlán ranch.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.